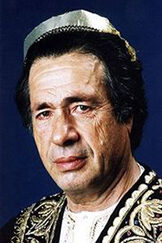

Rabbi Yosef Mammon c. 1741-1822

Many, although not all, commentators portray Rabbi Yosef Mammon (often spelled Maimon or variations thereof) as a “savior of the Bukharan Jews” and as perhaps the most influential individual in their long history. It was a long and winding journey that eventually brought Mammon to Central Asia. A descendant of the great Rabbi Moses Ben Maimonides (the Rambam), Mammon was born in Morocco. His father was a prominent rabbi, a prosperous jeweler, and a senior advisor to Moroccan royalty who was killed during political unrest. This led Mammon to move to Tsfat in the Land of Israel. The Jewish community in Israel had many difficulties at the time and Mammon, with his powerful connections, was quickly sent abroad to raise funds for the Holy Land. He went first to the Jews of Baghdad, then to the Bombay community, before making his way through Iran. It was there that he heard of a Jewish community that he believed needed rather than could provide help, namely the Jews of Bukhara. Accompanied by an interpreter familiar with Persian dialects, he arrived in the city of Bukhara around 1793.

He was not pleased with what he found. According to many sources, Bukharan Jews were at this time isolated from the rest of the Jewish world. The size of the community had dropped to around 5,000 and was concentrated in only one location, the city of Bukhara. Most commentators suggest that local Jews were increasingly ignorant and careless of Jewish law and lacked access to even basic Jewish texts. Others suggest that this picture of decline is overstated and that what most concerned Rabbi Mammon was that Bukharan Jews continued to hold tight to their own ancient Persian-based Jewish customs and religious authorities rather than to the ways found in Morocco and throughout much of the Sephardi Jewish world.

What is undisputed is that Mammon proved to be an energetic and influential figure. He spent the rest of his life in Bukhara, creating yeshivot that trained the next generation of local Jewish leaders and embarking on a literacy campaign among the entire community. He spread Jewish mystical ideas found in the Book of Zohar, founded an early Zionist movement, and secured support for Bukharan Jews from as far away as Lithuania.

He also succeeded in his aim of having Bukharan Jews abandon their traditional Persian nussach or style of prayer in favor of a more standard Sephardic liturgy. This was the result of a long and bitter campaign which threatened to split the community. Mammon’s triumph was aided by savvy marriage-alliances. One of his daughters had married the leading local rabbi while another married the community’s wealthiest figure.

After he died in 1822, many lauded Rabbi Mammon as the man who had saved the Bukharan Jews. Certainly, the community had changing significantly during his time. They were more closely integrated into the Sephardi Jewish world. Their numbers were growing, and by 1900 around 20,000 Jews lived in 30 or so cities around Central Asia. Even today, many Bukharan Jews refer to Rabbi Mammon as the Ohr Yisrael (Light of Israel) and as the Shandar (Emissary of the Rabbis).

Rabbi Shlomo Moussaieff 1852-1922

It might sound strange but walking through Jerusalem today is a good way to see the prosperity that the Bukharan Jewish community enjoyed at the end of the nineteenth century. Jerusalem’s Bukharan Quarter was established by wealthy Jewish emigrants, including Rabbi Shlomo Moussaieff, from what is today Uzbekistan but was then under the control of the Russian Empire. Moussaieff was born in the city of Bukhara and educated by the community’s leading rabbis before making a fortune in the tea trade and real estate. He is believed to have owned one of the city’s first banks and he and his family were later prominent in the jewelry and gem business.

His wealth reflected the new economic opportunities (and religious freedom) that Bukharan Jews, at least initially, enjoyed under the Russian Empire. Nonetheless, Moussaieff and many other Bukharan Jews, mainly for religious and Zionist reasons, began emigrating to Israel. “My spirit,” he wrote, “moved me to ascend to the Holy Land, the land in which our ancestors dwelled in happiness, the land whose memory passes before us ten times each day in our prayers.” Moussaieff arrived in Jerusalem in 1888 and started purchasing land and building houses and institutions in what would become the city’s Bukharan Quarter. It became one of Jerusalem’s most beautiful and affluent neighborhoods, renowned for its wide streets and lavish houses. Back in Uzbekistan, Moussaieff and the other Bukharan leaders had experienced newly Russified-cities and they insisted that the Quarter reflect the latest European architectural styles. One private house, which still exists today, was so impressive that it was known as the Palace. The Nobel-winning author Shai Agnon speculated that it was “built for the Messiah himself” and that, during the Messianic age, the kings of Jerusalem will live in a house built by “our brothers from Bukhara.”

Moussaieff’s own family compound or courtyard included homes, a synagogue, a ritual bath, a museum for his collection of rare Jewish manuscripts, and a housing complex he established for 25 poorer families from the community. By 1914, 1,500 Bukharan Jews lived in the quarter, which was a center of Bukharan culture, religious scholarship, and economic activity. However, the splendor and specific Bukharan identity of the Quarter would soon fade. Ottoman Turk rulers occupied some of its finest buildings during World War I, while the Soviet takeover of Central Asia from 1920 meant that Bukharan Jews back in Uzbekistan were both poorer and prohibited from moving to Israel. Some tried to escape to Israel but many starved or were killed along the way. Those who did make it to Jerusalem were often impoverished while the Quarter attracted an influx of Jewish immigrants from other lands. The Bukharan Quarter became dilapidated, overcrowded, and largely non-Bukharan. It is today a poor, predominantly ultra-Orthodox, area although signs of its wealthy Bukharan origins remain.

Moussaieff himself died in Jerusalem in 1922. A number of his seven children became prominent in the jewelry and gemstone trade around the world (despite his desire for them to remain in Israel). His grandson, also named Shlomo, become one of Britain’s richest jewelers while his granddaughter was the First Lady of Iceland.

Barno Itzhakova 1927-2001

Barno Itzhakova, one of the great singers of Central Asia, was born in Tashkent, the capital of what was then Soviet Uzbekistan. Her family were religiously traditional Jews. Her music reflected the multicultural nature of Uzbekistan at that time. She sang in the two major local languages of Uzbek (Turkic) and Tajik (Persian), but also in her Judeo-Tajik mother tongue of Bukhori, and in Russian, the language of Soviet rule and of the many recent immigrants into the area.

Known for her haunting, dignified voice, she was considered a “Queen of Shashmaqam.” It was an appropriate nickname as Shashmaqam was originally a royal music that had developed as a way to entertain the Emir of Bukhara and his court. It brought together Sufi poems of divine love and human despair with austere instrumentation provided by local instruments which resembled lutes, frame drums, and bass fiddles. Despite its connection with mystical Islamic traditions, Bukharan Jews were prominent in Shashmaqam, few more so than Itzhakova.

Itzhakova came to fame not in Uzbekistan but in the neighboring Soviet Republic of Tajikistan. Many Bukharan Jews at this time, including Itzhakova and her musician husband, were encouraged to move to its capital of Stalinabad (Dushanbe) which the Soviets were developing. Itzhakova also benefited from the fact that Shashmaqam was back in official favor. Communist rulers had generally suspected and at times suppressed the music, given its feudal, religious, and non-Russian heritage. But by the 1950s, it was seen as an important emblem of local culture worth encouraging.

Itzhakova took full advantage, becoming a star of stage, radio, and television. Experts compared her to some of the legends of the Shashmaqam past. She, like many other Bukharan Jews, played a major role in Central Asian cultural life despite considerable Soviet and local anti-Semitism. Itzhakova won many government awards, including the Soviet Order of the Red Banner of Labor.

However, in the uncertain, nationalist atmosphere that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, most Jews in both Uzbekistan and Tajikistan migrated. The situation in Tajikistan was especially volatile, with a bloody civil war. Itzhakova and her husband, also a singer, moved to Ramle, Israel. Her singing days were over but even in Israel, far from the Central Asian homeland of Shashmaqam, she was not completely forgotten. She died in 2001 but in 2017 the city of Petah Tikva named a street after her.

Ilyas Malayev 1936-2008

The poet and musician Ilyas Malayev was the equivalent of an Uzbeki rock star but ended his life suffering hard times and relative anonymity in New York. He was born in a small village in what is now the country of Turkmenistan but raised in a town near Bukhara (modern Uzbekistan). While still in his teens, he was considered a virtuoso in the tar and the tambur, string instruments similar to the lute, and in the violin. He mastered the traditions of the Central Asian music known as Shashmaqam through study with local teachers and by listening to recordings from the glory days of this music, which finished with the Soviet takeover of the region in 1920.

But by the 1950s, the Soviets were supporting rather than suppressing local folk music in their Central Asian territories. Malayev moved to Tashkent, capital of Soviet Uzbekistan, and became, in the words of one US writer, “about as successful as you could be in that part of the world.” A multi-talented artist, his shows combined traditional Shashmaqam with his own songs, poetry, and comedy. He performed widely at venues ranging from weddings to large stadiums with tens of thousands in the audience. Malayev became well-known outside of Uzbekistan and a national figure inside it. He played for the main state-controlled music ensembles and was often summoned, along with his wife who was a singer, to perform for visiting Soviet President Leonid Brezhnev.

Nonetheless, anti-Semitism and Communist control of the arts limited his creative freedom. Soviet and local rulers tried to freeze Shashmaqam so it did not reflect contemporary concerns or the Jewish identities of some its most famous practitioners, including Malayev. Malayev was also unable to have his poetry published. Written in TajikPersian, Uzbek-Turkic, and Russian, his poetry drew together melancholic references to his own life with praise to God. They occasionally included explicitly Jewish references. His poems would sometimes be read on Uzbeki television but without any reference to the fact that he, a Jew, had written them. The situation did not improve when the Soviet Union fell apart and former communists turned staunch Uzbeki nationalists took control.

Desperate to have his poetry published, in 1992 Malayev left Uzbekistan for the enclave of Bukharan Jews in Queens (or “Queensistan” as some locals call it) in New York. He was lionized by the local Bukharan community and continued to perform, write, and lead ensembles. Music scholars praised him as one of the few remaining experts of Shashmaqam in the world. Nonetheless, he was a man out of place and perhaps time. Two books of his poetry were translated but only self-published. He survived off welfare, sharing a three-bedroom apartment with nine others. He feared that Shashmaqam was disappearing both in Uzbekistan and in the Diaspora (UNESCO has recently declared it an endangered cultural practice). A US expert in Central Asian music wondered if Malayev was a “‘fool of God’ or simply a fool to have thrown in everything he had … for the sake of trying to publish his poetry?” It was a question that bothered Malayev. “Did I come here for nothing?” he asked once. He died in 2008.

Lev Leviev Born 1956

Lev Leviev, the so-called “King of Diamonds” and a legendary philanthropist whose fortunes have recently suffered a major fall, was born in Samarkand, Soviet Uzbekistan. His family were prominent members of the Bukharan-Jewish community, and he remembers his childhood as being dominated by “fear” of both local and Soviet anti-Semitism. From a young age, Leviev was determined to become rich. “I knew from the time I was 6 that I was destined to be a millionaire,” he later commented.

In 1971, his family moved to Israel when the USSR temporarily loosened restrictions on Jewish emigration. They lived in the impoverished town of Kiryat Malakhi. Leviev left his Chabad religious school at age 15 to work in a diamond-polishing store. Determined to master all parts of the diamond business, he attributes his ability in diamond-cutting to steady hands and the skills he picked up while learning how to perform ritual circumcisions. Fiercely ambitious, Leviev rose to a senior position in the De Beers diamond cartel. He then struck out on his own, determined to break De Beers’ monopoly of the world diamond market and to get access to uncut diamonds.

After receiving the blessing of the leader or Rebbe of the Chabad Hasidic movement, Menachem Mendel Schneerson – to whom he remains devoted to – Leviev began doing business in the Soviet Union during the last, chaotic days of communist rule. But it was in the capitalist “wild west” of Russia immediately after the fall of the Soviet Union that Leviev made his mark. He established a close friendship with President Vladimir Putin and following that with Angolan leader Jose Eduardo Dos Santos. He owned diamond mines in Russia, Angola, and Namibia, was the world’s largest cutter and polisher of diamonds, and sold the diamonds in his upmarket stores around the world. In 1996, he purchased the Africa Israel Investments Ltd. (AFI Group) and built up vast interests in real estate, chemicals, steel, energy, and fashion. He owned the former New York Times building, million-square-feet Russian malls, and what was said to be Britain’s most expensive private home.

By 2007, he was reputed to be Israel’s richest man and the most generous Jewish philanthropist since Moses Montefiore. He donated an estimated $50 million a year to Jewish causes, especially in the former Soviet Union where he supported over 500 Jewish communities, including in Uzbekistan. His financial support helped Chabad assume a dominant role in Jewish communities around the former Soviet Union.

Leviev’s business empire has suffered some blows in recent years. After the global crash of 2008, AFI Group fell into massive debt and was eventually sold and deregistered from the Tel Aviv stock exchange. The company owed billions but Leviev remains a wealthy man and a big player in the diamond world. However, his preference for staying out of the headlines was challenged by allegations of exploitation and corruption in relation to his diamond mines in Angola in particular, while his building programs in the West Bank have also sparked some unease. Leviev’s ties with Putin, the Trump Organization, and Jared Kushner attracted the interest of Robert Mueller during the investigations into alleged Russian interference into the 2016 US presidential elections.

In 2018, two of Leviev’s sons, his brother, and other members of the Leviev organization were arrested in Israel on charges of diamond smuggling. Shortly afterwards, an employee fell to her death in mysterious circumstances from Leviev’s Tel Aviv office building. The Israeli police sought to question Leviev about smuggling, money laundering, and tax evasion. Leviev denied any wrongdoing but has so far declined requests to return to Israel from Russia, where he now lives.

J2 STUFF.

We have everything you need to know before you go. Check out our Instagram my_j2adventures for cool updates and interesting tidbits.

The J2 App

available on the App Store & on Google Play.

START PLANNING LET’S EXPLORE.

Whether you have a journey in mind, want to join a featured trip, or simply want to explore, drop us a note. We work really hard to be a loved travel company that delivers amazing and memorable experiences. So please do not be surprised when we say “yes” to every reasonable request you make!