Philo c. 20 BCE - c. 50 CE

Sometimes called the “Jewish Plato,” Philo of Alexandria’s attempts to show that Greek philosophy and Judaism were compatible changed both religion and philosophy. We know only fragments about him including that he lived in Alexandria and was from an elite Jewish family. Indeed, his brother was so wealthy that he lent huge sums to the wife of the Roman statesman Agrippa and provided the gold and silver that lined the huge gates of the Temple in Jerusalem.

The city of Alexandria during the first century CE was home to one of the ancient world’s largest Jewish communities as well as having a sizeable Greek population and a rich Greek culture. Philo, like many local Jews, was connected to both traditions. He spoke and wrote in Greek, the dominant Jewish language of the city, and studied the Torah in the Septuagint’s Greek translation rather than in Hebrew. He was a pious and observant Jew who made the festival pilgrimage to the Temple in Jerusalem but was also a fan of Greek theater, boxing, and chariot racing. What was more unusual, even unique, were his attempts to create a philosophical-theological basis for this synthesis. He sought to explain the Jewish religion to Greco-Roman intellectuals but also to convince religious Jews that Greek philosophy and Judaism stood for “practically identical purposes.” (He was, it must be said, rather less enamored of Egyptians and their polytheistic traditions.)

Philo’s work was daring but dense. One modern commentator argues that his writing was so rambling, humorless, and obscure that Philo may have been deliberately trying to put off all but the initiated few. A major branch of his writings were discussions on Jewish law and allegoric commentaries on the Torah which revealed the influence of Greek thinkers, especially Plato. He also created philosophical and religious treatises including an argument in favor of the Stoic idea that only the wise are free. His writing on contemporary issues included a condemnation of “mob rule” that defined true democracy as a form of government in which all men are equal before the law.

Greek and Jewish coexistence did not last in Alexandria, especially once the Romans took control over the city. In 38 CE, in what is sometimes called the first major pogrom in Jewish history, the Greeks of Alexandria rioted, killing many Jews and mocking Jewish traditions. Shortly afterwards, Philo went to Rome where he tried unsuccessfully to convince Emperor Caligula to ignore Greek accusations that the Jews of Alexandria were disloyal. By the end of the first century, Rome had virtually destroyed the great Jewish community of Alexandria while hostility to Judaism and Jews was becoming commonplace in Greco-Roman philosophy.

Nor did Philo’s work leave much of a mark on his Jewish co-religionists. Ironically, he had more influence on early Christian theologians (some of whom thought Philo was a Christian) than on rabbinical Judaism. Nonetheless, Philo is recognized today as the first thinker who tried to synthesize religious faith and philosophic reason. He is seen as a vital part of the process in which “philosophy turned religious and religion philosophic.”

Maimonides c.1135-1204

The philosopher, physician, and legal authority Rabbi Moses Maimonides (the Rambam) was one of the great figures in all of Jewish history. He was born to a prominent rabbinical family in Cordoba as the Golden Age for Spanish Jews began to slip away. Fearing they would be forcibly converted to Islam after the fanatical Almohad dynasty took power in 1148, he and his family fled. By around 1166, Maimonides was living in Fes, Morocco, where he trained as a physician and wrote one of the first systematic commentaries on the Mishnah.

The Almohads also persecuted Morocco’s Jews and by 1168, Maimonides had escaped to Egypt. He fell into a deep depression after the death of his brother David but recovered to become the personal physician to the royal family and Nagid or head of the country’s Jewish community. Although his medical and philosophical works emphasized the importance of moderation and a healthy lifestyle, Maimonides the physician kept a hectic schedule of treating the sultan and his court during the day before returning home to tend to dozens of Jews and non-Jews into the night.

He somehow also found time to write ten important medical books, and to author the Mishneh Torah. This monumental summary and codification of all Jewish law was criticized by some who thought that Maimonides was attempting to replace and surpass the Talmud. Also groundbreaking was his Guide to the Perplexed which daringly combined Aristotelian and Islamic philosophy with Jewish teachings. Maimonides’ rationalist approach – including his insistence on the non-corporeality of God and his views regarding the resurrection of the dead – both influenced and outraged contemporary Jewish and non-Jewish thinkers. Like many of his works, it was written in Arabic and reflected Maimonides’ knowledge of Islamic and Arabic philosophy and sciences.

He died in Cairo in 1168 and was buried at what is today the Maimonides synagogue in Cairo’s Jewish quarter. His body was later taken to Israel, but for centuries, ailing Jews would visit the Cairo synagogue believing that it possessed miraculous healing powers. Maimonides, who was staunchly opposed to what he considered superstition, would have been appalled. The synagogue has recently been renovated by the Egyptian government.

Renowned if controversial in his lifetime, his reputation grew over the centuries. His work today is still widely studied and lauded as a highpoint in Jewish thought and religious scholarship. As a popular Jewish expression puts it: “From Moses [of the Torah] to Moses [Maimonides] there was none like Moses.”

Leila Mourad 1918-1995

Born Lillian Mordechai, Leila Mourad was a superstar of Egyptian film and music and one of the Jews who played a major part in twentieth-century Arab culture. However, her career was derailed in the 1950s following rumors that she was a Zionist, a telling sign of the increasing difficulties facing Egyptian Jews after the establishment of the State of Israel.

Leila came from a Cairo showbusiness family. Her Iraqi Jewish father, Zaki Mourad, was a well-known singer and cantor. Her mother was from a Polish Jewish background. Not unusually for an Egyptian Jew, Leila attended a Christian convent school but when her father left to tour the Arab world and America, she was forced to work as a seamstress to help sustain her mother and her six siblings. After seven years away, her father returned to find a new style of Arabic music was in the ascendancy. He began to tutor and promote Leila. From the age of 14, she appeared in concerts throughout the country and thrived with the spread of radios and gramophones. She would go on to record over 1000 songs and is considered one of the great vocalists in a golden period for Arabic popular music.

Grasping the new opportunities that were opening up for some women in 1930s Egypt, Leila also starred in hugely popular films. Many of her 27 films were titled after her, including Leila, the Girl from the Country and Leila, Lady of the Camelias, both made with the Egyptian-Jewish director Togo Mizrachi. It was on set that she met the actor and director Anwar Wagdi, the man some have labeled “her lover and nemesis.” Against her father’s objections, she married Wagdi, a Muslim, in 1945. Their wedding ceremony was included in the film Leila, the Daughter of the Poor. In 1947, as anti-Semitism rose in the country, Leila converted to Islam, an event widely covered by the Egyptian press. Her onscreen relationship with Wagdi was popular with film fans but off-screen proved tumultuous. According to some sources, they married and divorced three times in quick succession.

By 1952, Leila was closely identified with Egypt’s new military regime led by Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser. The media called her the voice of the Egyptian revolution and she (briefly) married one of the architects of the military coup, Waguih Abaza. But given Egyptian hostility toward Israel, her Jewish background remained an issue with the public. Rumors began to appear in the press (apparently started by her embittered ex-husband Wagdi) that she had donated large sums of money to Israel and visited family there. Her songs and films were banned in much of the Arab world. The Egyptian press and regime eventually rallied behind one of the country’s most popular stars, denying the claims and printing photos of her holding the Koran and articles proclaiming her a loyal Egyptian Muslim. Only Syria maintained the boycott, but they too dropped it, apparently on Nasser’s insistence, when the two countries temporarily united in 1958.

Nonetheless, Mourad’s career was damaged and her great singing rival Umm Kulthum increasingly dominated the airwaves. In 1955, Mourad abruptly retired. She maintained an almost total public seclusion for the last decades of her life. Nonetheless, interest in her and her religious affiliation continued to be strong. Apparently estranged from her Jewish family, she was reported to have refused to visit a brother who was, like many Egyptian Jewish men, arrested and tortured following the 1967 Six Day War, or to see him before he was expelled from the country. When she died in 1995, her sons were careful to tell the press that she received a Muslim rather than a Jewish burial. Despite all the controversy, her songs remain popular in Egypt today. In 2009, millions tuned in to an Egyptian-Syrian television series about her life.

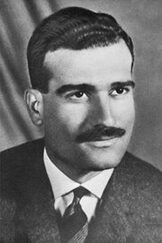

Eli Cohen 1924-1965

Befitting his reputation as Israel’s greatest spy, there are many stories about Eli Cohen but not all of them are verifiable. What we do know is that the man whom the highest echelons of Syria’s leadership considered a patriotic Syrian Muslim was in fact an Egyptian-born Jew working for Israel.

Cohen came from a Zionist family from Alexandria. In 1947, as Egyptian Jews faced increasing persecution and suspicion, Cohen’s efforts to join the Egyptian army were rebuffed and he suffered harassment while studying engineering at Cairo’s Farouk University. His family left for Israel in 1949 but Cohen stayed to complete his degree and to carry out Zionist activities. He played a small part in an Israeli-initiated spy ring of Egyptian Jews that was uncovered in 1954. Two of his colleagues were executed. Cohen was arrested and interrogated, then released.

In 1957, Cohen emigrated to Israel. Fluent in Arabic, French, and English, he held a “desk job” as a translator for Israeli military intelligence. Despite his intelligence, bravery, and remarkable memory, he was rejected from more elite Mossad operations out of fears that he had an “exaggerated sense of self-importance” and a penchant for risk-taking. The angered Cohen left the intelligence world for a poor-paying job as a filing clerk but by 1960, Mossad wanted him for a high-risk, undercover operation in Syria. Married with a young family, he eventually agreed, undergoing intense training in everything from weapons and radiocommunications to Koranic studies. Particularly important, he learned to speak Arabic with an impeccable Syrian rather than Egyptian accent.

Cohen was sent initially to Argentina where he established his new identity as Kamel Amin Taabeth, a rich businessman-playboy of Syrian extraction. Using his considerable charm and the large funds invested by Mossad in the operation, he befriended many Syrian movers and shakers stationed there, including, it is claimed, the future Syrian president Major Amin al-Hafeez. In 1962, with a radio transmitter hidden in his luggage, Cohen-Taabeth was sent to Damascus. He proved a remarkable hit. His lavish parties, with their generous supplies of alcohol and attractive women, were popular with Syria’s military and political elite. Cohen overheard drunken secrets, was given access to classified information, and was invited to Syrian military facilities. He helped the IDF destroy a Syrian plan to divert water from northern Israel. It is said that he convinced the Syrian military to plant Eucalyptus trees near their hidden fortifications on the Golan Heights so that their soldiers could enjoy the shade. The trees proved an ideal target for future Israeli bombardments.

By 1964, Cohen feared that he was under suspicion. He returned to Israel, spent time with his family (who remained unaware of his Syrian alter ego) and indicated to his superiors that he was ready to rejoin normal life. Syria was considered nearly impenetrable to Israel’s intelligence and therefore he was pressured to return. Back in Syria and with war between the two countries looming, the always brave Cohen became reckless. He sent many radio transmissions in a short period, often at the same time of day. In 1965, he was captured, perhaps due to Soviet security experts working with Syrian counterintelligence. Despite pleas from Israel, world leaders, and the Pope, Cohen was hanged in Damascus in front of a large crowd of jeering onlookers. His body, with anti-Zionist slogans attached to it, was left hanging for six hours. In his last moments of life, he had written to his wife, begging her not to weep.

A man of the shadows during his lifetime, in death Cohen became an Israeli hero. Many believe that his information was crucial to Israel’s rapid conquest of the Golan Heights during the Six Day War of 1967. The Prime Minister attended the bar mitzvah of his son; streets were named after him. Netflix recently made a series about him called The Spy. But still, despite 45 years of requests, Eli Cohen’s remains have not been returned to Israel and to his family.

André Aciman born 1951

The writer André Aciman, whose novel Call Me By Your Name is considered a classic of gay literature, has also written superbly about his experiences growing up in Egypt. His father’s Sephardi family included a rich cast of feuding but close-knit eccentrics including a rakish conman uncle who was at various times a Prussian military officer, an Italian fascist, and a British spy. The Aciman clan were predominantly Turkish with strong links to Italy but settled en masse in Alexandria from 1905. This was a time when many Jews were prospering in Egypt and the Acimans had a valuable advantage: André’s great uncle was best friends with Prince (soon to be King) Fuad. The extended family indeed did well in Egypt as bankers and businessmen. Aciman’s father owned a textile factory while his mother also came from a wealthy Sephardi background. Aciman has written movingly about his mother’s life as a deaf woman in a time and place when deafness was considered a stigma.

Aciman grew up in a cosmopolitan, multi-national, religiously eclectic Alexandria that “existed for a short time and then disappeared.” French, Italian, Greek, Ladino, and (less frequently) Arabic were spoken in his home while he, like many wealthy Egyptian Jews, attended an English-speaking school. Aciman never felt fully Egyptian but enjoyed a privileged life of “daily trips to the beach, visits to the tailor for custom madesuits, tennis lessons and tutors.” After the 1956 Suez war, that sense of ease disappeared as anti-Semitism and Egyptian nationalism surged. Most “foreigners” and Egyptian Jews, including many of Aciman’s extended family, fled or were expelled. Aciman and his parents stayed but as the only Jewish boy remaining in his school, he was subject to sustained abuse. By 1965, his parents’ businesses and properties had been confiscated and they were kicked out. Aciman writes about his last night in Alexandria that “what made leaving so fiercely painful was the knowledge that there would never be another night like this” as “I caught myself longing for a city I never knew I loved.” Aciman’s books, especially his non-fiction, would deal obsessively with exile and displacement, his sense of being “a man without a country.”

After a painful period as refugees in Italy and France, Aciman and his mother moved to the US in 1968. He completed his Ph.D. at Harvard and taught creative writing at various universities. After a long period of feeling “too foreign” to write in English, in 1995 he penned his family memoir Out of Egypt. It won the Whiting Award.

Apart from exile, Aciman’s other great literary themes are desire and sexual fluidity. His first novel, Call Me By Your Name (2011) about a summertime relationship between two young Jewish men was a literary sensation with rave reviews, awards, and large sales. Although set in Italy, it was inspired by the Alexandria he once knew. The novel, he said, was an “idealized Egypt, as it is refracted by memory, by imagination, by fiction.” In 2017, it was made into a successful, Oscar-winning movie. The sequel Find Me was published in 2019.

Saadia Gaon 882? - 942

We have seen that Philo attempted to tie the Jewish tradition with the Greek language and culture. More than 800 years later, another Egyptian Jew, Rabbi Saadia Gaon, would prove even more influential by integrating Judaism with Arabic and Arab philosophy.

His given name, Saadia, an unusual Hebrew version of the Arab name Sa’id, was an early indication that he would have a foot in both worlds. Later, some of his Jewish enemies – of which there were many – would use his name as part of their claims that Saadia’s father was an Arab Muslim. But in reality, it would seem that his father was a Jew and a rabbi. Saadia was born in the village of Fayyum in upper Egypt, probably in 882. By 912 he had written his first great work, a Hebrew dictionary and grammar, the first of its kind.

Saadia was a notoriously strong-willed character and a keen participant in the Jewish rivalries of his day. He wrote a full-frontal attack on the Karaites – a significant Jewish group in Egypt and elsewhere who accepted the Torah but not the Talmud – and other “heretics” opposed to rabbinical Judaism. This led to his house being ransacked. Fearing for his life, Saadia fled from Egypt to Israel.

Saadia also became embroiled in the battle for primacy between the leaders of the Israel and Babylonian Jewish communities. By 922, this rivalry had reached a new peak. The immediate issue at hand were technical matters involving the Jewish calendar, but the potential ramifications were vast. Rabbis from the land of Israel insisted on an alternative calendar to that laid out by the Babylonians. The result would be that the two major Jewish communities of their time would celebrate the Jewish holidays on different days. The dangers of schism were real. Saadia, an expert astronomer, bolstered the Babylonian position, writing an important book explaining the arguments. The different camps did indeed observe the Passover of 922 on different days but by Rosh Hashana (the Jewish New Year), the Israel rabbis had given way and unity was restored.

This success led Saadia to being appointed the Gaon or leader of the Babylonian yeshiva at Sura, one of the most prestigious positions in the early medieval Jewish world. True to form, he soon clashed with the man who appointed him, the exilarch or secular leader of the Babylonian Jewish community. The exilarch was accused of a conflict of interest in judging a property dispute case which he stood to benefit from. The two men excommunicated each other, the community was split, violence was threatened. Saadia was forced to leave his post for a number of years but eventually there was reconciliation and Saadia resumed his role as Gaon.

Despite all the disputes, Saadia still found time to write a large number of innovative and important works. As the first major rabbi to write in Arabic rather than in the customary Hebrew or Aramaic, he founded the Judeo-Arabic literary tradition that would flourish in later centuries. He carried out the first Arabic translation and commentary of the Torah and of the Tanach. At this time, most Jews in the Arab world spoke Arabic as their primary language. Many were drawn by Arab philosophy. It has been argued that Saadia’s superb Arabic prose and use of Arab (and Arab-filtered Greek) philosophers and scientific knowledge to explain Jewish texts and ideas helped keep many Arab-speaking Jews connected to the Jewish tradition. He also produced the first systematic explanation of Jewish dogma and faith. Saadia’s radicalism, rationalism, and connection with “foreign” philosophers angered some Jews. But he inspired others, including, 200 years later, Rabbi Moses Maimonides, another great rationalist and polymath with links to Egypt.

Nonetheless, this life of frantic creativity and strife took a toll. Saadia Gaon suffered repeated illnesses and died in 942 of “black gall” (melancholia).

J2 STUFF.

We have everything you need to know before you go. Check out our Instagram my_j2adventures for cool updates and interesting tidbits.

The J2 App

available on the App Store & on Google Play.

START PLANNING LET’S EXPLORE.

Whether you have a journey in mind, want to join a featured trip, or simply want to explore, drop us a note. We work really hard to be a loved travel company that delivers amazing and memorable experiences. So please do not be surprised when we say “yes” to every reasonable request you make!